Bett Williams in California, smiling among juniper branches

In the high desert south of Santa Fe, Bett Williams lives with her partner and their four dogs. For three years, they ran their own store in a small coal town where they sold psilocybin-mushroom T-shirts, LSD pendants, and psychedelic-inspired pencils labeled with the names of entheogenic plants. Bett, however, wasn’t born a psychedelic lifer. Her journey with plant medicines – psilocybin mushrooms in particular – has been varied and complex.

Conversation with Bett is easy, familiar; her voice is smooth and grounded. It is rare to talk to strangers and sense their comfort in the quiet in-between, but Bett has a way of holding space in every moment.

Her first encounter with psilocybin was completely random and occurred at exactly the right time. In a 2018 article for Lenny Letter, she describes it as “everything one would want from a first-time experience. I went to sleep blissfully, having visions of insects and dirt, tears streaming down my face in gratitude.” When she told her supervisor the next day (a woman with whom she was having a complicated affair, Bett age 15, her supervisor 28), it cost Bett the job. It was work she really loved, work that brought her purpose. “It really messed me up,” she recalls, “and I had a block against psychedelics until much later in my life.”

Designed by artist, art framer, and woodworker, Beth Hill

Bett, a published novelist with a forthcoming book detailing her journey into psychedelic exploration, mentions psilocybin as a catalyst for renewing her creativity. “I was blocked for a solid fifteen years – I couldn’t finish a book, I was in a bad relationship, and I crashed into mushrooms.” From a quiet inner place, she turned to a friend and asked for mushrooms. That’s how her practice began; she started taking a low dose by the fire every two weeks.

Her reintegration was very healing, and the mushrooms became her muse, redirecting her artist’s path. At certain points, she found it too difficult, giving up two different times but remembers, “I really had nowhere else to turn. When you’re committed to writing a book about mushrooms you kind of have to take them.”

This intensive immersion steered Bett to a high-dose psilocybin, Afrofuturist group in Cleveland. There she met Kai Wingo, an urban farmer and leader of the community. Kai, who passed away in 2018, was a huge champion of Bett’s exploration. “She gave me the idea I could speak about these things, that I was worthy, so she invited me to speak at her conference. I realized the mushrooms are a very rogue people’s movement.”

With friend and author of Your Psilocybin Mushroom Companion, Michelle Janikian, at Luz Eterna Retreats, Puerto Escondido, Mexico.

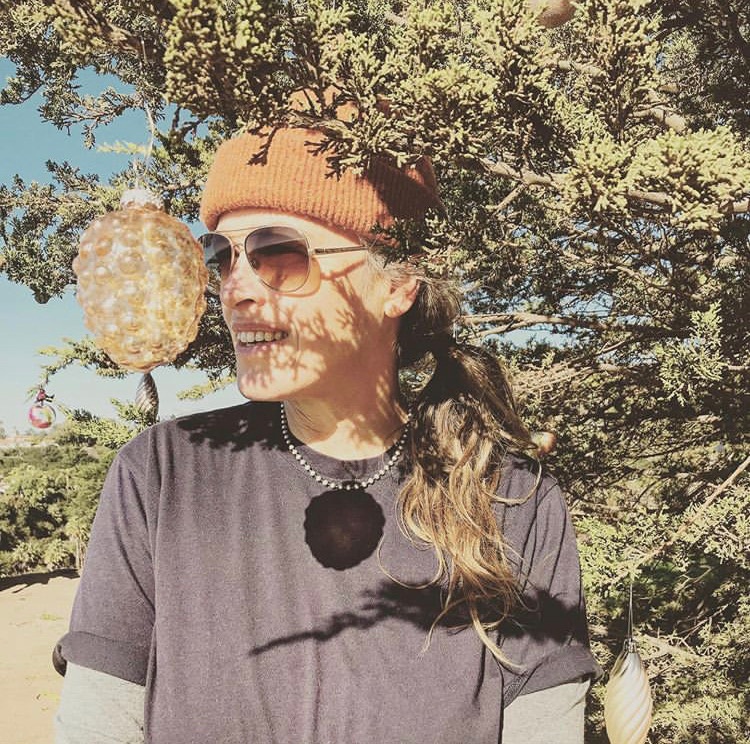

The mushrooms also brought her to an elder Mazatec curandera, Alma, in Huautla de Jiménez, Mexico. She writes, “it was my desire to honor the psilocybin mushrooms as the Mazatec do, not as a pharmaceutical helper, a pleasure drug, or even a tool of self-discovery in the Western psychological sense. I wanted to honor them as a holy sacrament.”

This earnest desire to respect the sacred teachings and ceremony led Bett to grow them in her home for many years. As a public figure today, she no longer is willing to take that risk admitting, “it’s too dangerous,” but she never stops being grateful for how they found her again.

“It really is a medicine for the people. It’s a folk medicine. We’ve been doing it since we don’t even know – a long, long time ago!”

In 2018, Bett was a speaker at the Horizons Conference and served as a moderator for the Cultural and Political Perspectives on Psychedelics in San Francisco. “Part of the movement,” she states, “is that they always want a rogue user who says, ‘you can go out and do it on your own,’ like literary writers such as Tom Robbins, who came out in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I come out of that tradition. That’s what I stand for.”

“If someone asked, ‘what am I?’’ and ‘what is the thing of it all?’ I would say, I’m the culture maker. I’m the trickster.” Bett lives that way; she lives rogue. She doesn’t believe you need to be part of an institutionalized revolution, or that you need a medical professional approving each of your moves. To be clear however, she doesn’t suggest against it either.

“I know my role with the mushrooms is a big one because there aren’t many people fully standing for rogue.” Bett is grateful to have the support and friendship of ethnobotanist, Kathleen Harrison, who says, “there is no psychedelic without culture.” Bett embodies her friend’s words, this mindset that plant medicines truly can connect people, bridge gaps, and build a vast mycelial network.

Traveling with her partner, Beth Hill.

Bett has used psilocybin mushrooms around 200 times over the course of 10 years. “My whole thing is, I really encourage people not to stray far from their own life. You don’t need to go far away and join a group – just see what’s close to you and go with that. The nature and power of the mushrooms make it so each person needs to find a way that really works for them.”

Having worked with psychedelics for many years now, Bett acknowledges it’s still possible to overdo it, that you can surpass your own limitations. “These definitely aren’t things beginners need to worry about, but I continue to be given answers about things I can’t really do again… In terms of what groups are doing in a clinical setting, I have met many people who say it’s the only way they can do it. That’s very humbling because, for me, these things are meant to be done in nature, the old ways,” but she repeats, “that’s just me.”

She is not judgmental and listens when people share their experiences different from hers, saying, “the mushrooms have their own path.”

“Psychedelic space is such a vulnerable space so if I lay a big trip on how other people should do it, it’s going to infect my own relationship with the mushrooms.”

She encourages anyone interested in learning about plant medicines in clinical settings to “be careful: The moment you give somebody power over you, psychedelics are just going to exaggerate that even more.”

Regarding the future of the movement to decriminalize and ultimately legalize psilocybin and other plant medicines, Bett gently reminds people to be mindful of the history of the pharmaceutical industry. Having spoken to a number of veterans in her years on the circuit, she recalls a former soldier saying, “they’re always experimenting on us… Why can’t they just leave us alone and let us take care of ourselves?”

Bett back home in New Mexico.

Now is the third wave for psychedelics, as Bett sees it. There were the sixties of Timothy Leary and Ram Dass, the Vietnam War protests and free love, psychedelic writers and merry pranksters. Then, there was the tech boom of Northern California, the time of ‘cyberdelic’ and Mondo 2000, the merging of psychedelic Burning Man and Silicon Valley. Today, Bett believes, “this could be the third wave… and it’s definitely spearheaded by medicalization. While people have been doing this for a long time, we are definitely seeing a resurgence. It’s gonna’ happen. A lot of people are going to be using mushrooms in many different settings.”

When asked how she participates in working with different medicines today, she speaks to the benefits of low-dose LSD, something she enjoys in public. “I regard it with the same love and respect I hold for the other medicines.” In contrast, she no longer does mushrooms out in the world “because it’s so much about healing: physical healing, spiritual healing. I always have Guadalupe on my altar. I burn a lot of juniper and copal. Sometimes I play Maria Sabina songs, sometimes I don’t. I just follow where the medicine takes me, and I do that every six months or so these days.

“For me, it’s about ceremonies at home. I will share an experience with my friends who are creative people – filmmakers, writers – and it’s a different kind of ceremony because we sit around and develop our projects and increase our bonds with each other, and with our art.”

Her experiences with ayahuasca (over the course of nine ceremonies) have also been influential in her life. “I find that grandmother medicine to be more effective in working on my alcohol addiction issues than the mushrooms have been. The structure of an aya ceremony requires that I let go more to the group and the person holding the space. This helps me go deep in a way I sometimes cannot with my secular mushroom use. I really appreciate the purge in the ayahuasca ceremony.

“I also have worked with San Pedro. I turn to it when I feel like I need deep physical healing – gut, muscle and organ healing.” She believes in using cannabis edibles for helping with the physical pain as well, especially for hormonal changes and sleep assistance.

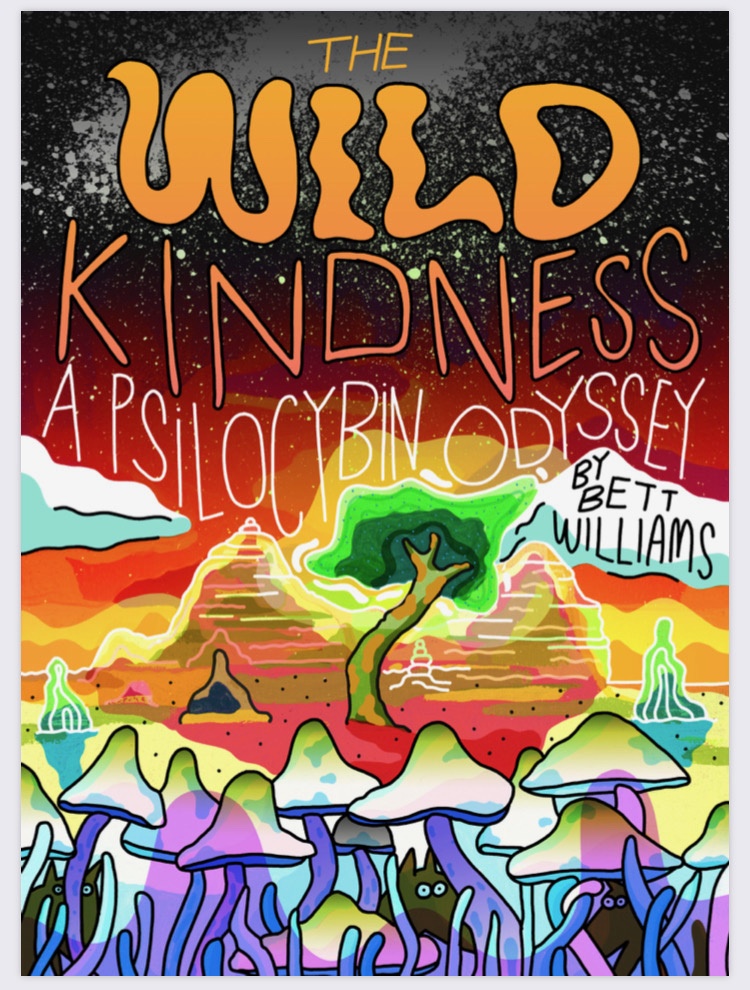

Bett’s book, The Wild Kindness, will be released by Dottir Press in September of 2020 (cover art by Mike Perry).

She was gracious enough to discuss her new book, The Wild Kindness and what it means to her: “This was big for me. I almost didn’t finish and a writer that doesn’t write is kind of f*cked. This book is about saving my own life and doing what I came here to do.”

“That’s the way of the mushrooms. They never asked anybody to write it down,” she jokes, “but they do seem to want me to write it down.”

She said it before, and she’ll say it again: “psilocybin mushrooms gave me a creative life again. They gave me my life back.”

Through her writing, by being honest in public about her experiences and by remaining truthful to her journey, Bett has helped a number of people across the United States, if not the world.

We look forward to celebrating your work! Thank you, Bett Williams, for embodying what it means to live a psychedelic life. Thank you for your creativity, humility, strength, and inspiration!

Would you like to help spread our message and support the #ThankYouPlantMedicine movement as a volunteer? Please click here for more details.

* DISCLAIMER & IMPORTANT SAFETY MESSAGE

The #TYPM movement does not encourage any illegal use or abuse of plant medicines and psychedelics, whether cultivated in nature or lab synthesized.

Psychedelics and plant medicines – even within the confines of applicable laws – are not appropriate or beneficial for everyone. They are not magical cures, but are tools that when used properly – with respect, clear intentions, guidance, and a safe, supportive environment – can catalyze personal growth and healing.

To minimize harm and increase therapeutic potential, it is imperative that one performs sufficient research, adequately prepares, and integrates their own experience.

This interview was published in February 2020 by Anne Lyons. It was edited for length and clarity.